- Home

- Philip P Choy

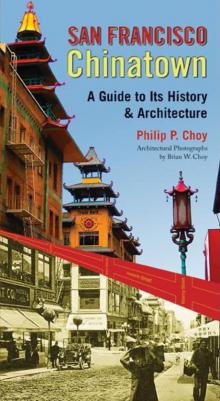

San Francisco Chinatown

San Francisco Chinatown Read online

SAN FRANCISCO

Chinatown

A Guide to Its History

and Architecture

Philip P. Choy

Architectural Photographs

by Brian W. Choy

City Lights • San Francisco

Copyright © 2012 Philip P. Choy

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Choy, Philip P.

San Francisco Chinatown : a guide to its history and architecture / Philip P. Choy.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-87286-540-2

1. Chinatown (San Francisco, Calif.)—Tours. 2. Chinatown (San Francisco, Calif.)—History. 3. Chinatown (San Francisco, Calif.)—Description and travel. 4. Chinese Americans—California—San Francisco. 5. Historic sites—California—San Francisco. 6. San Francisco (Calif.)—Tours. 7. San Francisco (Calif.)—History. 8. San Francisco (Calif.)—Description and travel. I. Title.

F869.S36C4717 2012

979.4’61—dc23

2012012592

City Lights Books are published at the City Lights Bookstore 261 Columbus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94133

www.citylights.com

This book is dedicated to the late Him Mark Lai,

Dean of Chinese American History.

CONTENTS

Preface

Acknowledgments

Introduction

HISTORY

Spanish Period

Mexican Period

American Period

Chinatown Beginnings

Anti-Chinese Politics

Earthquake

Chinatown Post-Quake

Politics of China in Chinatown

Born American of Chinese Descent

PORTSMOUTH PLAZA

Chinese Culture Center

Manilatown and I-Hotel

Walter U. Lum Place

Wing Sang Mortuary

Everybody’s Bookstore

Chinese for Affirmative Action

Chinese Congregational Church

SACRAMENTO STREET

Chy Lung Bazaar

Chung Sai Yat Po

Chinese Chamber of Commerce

Yeong Wo Benevolent Association

Nam Kue School

Chinese Daily Post

Chinese Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA)

Willie “Woo Woo” Wong Playground

Chinese Baptist Church

GRANT AVENUE

SOUTHERN GRANT AVENUE

Sing Chong and Sing Fat

Old St. Mary’s Church

St. Mary’s Square

CENTRAL GRANT AVENUE

Sidewalk Stalls

Streetlamps

Chinatown Squad

Cathay Band

Jop Faw Poh (General Merchandise)

Food Facts and Fables

Herb Shops and Herb Doctors

The Chinese World

Soo Yuen Benevolent Association

Loong Kong Tien Yee Association

Chinese Telephone Exchange

Sam Yup Benevolent Association

Yan Wo Benevolent Association

NORTHERN GRANT AVENUE

The Mandarin Theatre

City Lights Bookstore

Pacific Avenue

STOCKTON STREET

Chinese Hospital

Chinese American Citizens Alliance

Chinese Episcopal Methodist Church

Gordon J. Lau Elementary School

Gum Moon Residence

Chinese Presbyterian Church

Hop Wo Benevolent Association

St. Mary’s Chinese Mission

The Chinese YWCA and YWCA Residence Club

Donaldina Cameron House

Chinese Central High School (a.k.a. Victory Hall)

Chinese Consolidation Benevolent Association (a.k.a. Chinese Six Companies)

Kong Chow Benevolent Association

Kuomintang (KMT)

ROSS AND SPOFFORD ALLEYS AND WAVERLY PLACE

Golden Gate Fortune Cookies Co.

Chee Kung Tong

Tien Hou Temple and Sue Hing Benevolent Association

Ning Yung Benevolent Association

WALKING TOURS

Works Cited

Selected Bibliography

PREFACE

From the time of the Gold Rush of 1849 to the present, Chinatown has been a “must-see” in every guidebook on San Francisco. Chinatown in the 19th century was singled out as a blight on the urban landscape of the city, its infamous reputation spreading to the far corners of the nation. Visitors were warned not to wander alone but were advised instead to hire licensed guides for safety. Only the guides could take you through the maze of secret underground tunnels into the bowels of the earth, where you could witness a “peculiar” race dwelling in darkness.

Descriptions of a mysterious Chinese quarter were so compelling that John W. Wilson, a young man from a small village east of Indianapolis who joined the army during the Boxer Rebellion, returned home via San Francisco, determined to see Chinatown. In an oral history taken in 1969 by Thomas Krasean of the Indiana Historical Society, Wilson recalled his experience.

JW: And I come over to Frisco and we all wanted to see Chinatown, there was ten of us. So Chinatown was underground at that time, you know … City underneath. Did you never read about that? Boy, beat anything you ever saw in your life.

TK: Actually underground, you mean?

JW: Actually underground, business houses … opium dens and everything else down in under there. Well, we were standing in front of this agency waiting for a guide … there was a Chinaman walked up … and said, “I am a guide… .” Well we hired him. We got underground and we went in a saloon … down a stairway and then … he says, “Now, you are underground… .”

The remainder of the interview tells how the guide, who held the only torchlight, vanished and left them wandering in the dark. While desperately searching for a way out, Wilson’s friend nearly stepped through a trap door and if he had fallen through, he might never have been heard from again. According to Wilson, this was the way people were robbed. After their horrifying experience, he and his friend finally found their way out in the morning. The rest didn’t get out until later that evening.

John Wilson continued:

But everybody had a different experience from the other fellow … wandering around, told they get into … opium dens and everything else, you know. Underground … that was underground before the earthquake. When the earthquake … thousands of people died under there that nobody ever known about.

These images of an infamous Chinatown began to change after the 1906 Earthquake. Guides applying for licenses issued by the police commission were warned not to refabricate and promote the evil spectacle of an underground Chinatown, lest their licenses be revoked. Public opinion began to improve, aided by a series of positive articles run by the San Francisco Chronicle. The Chinese also promoted this improvement by planning a new Oriental City.

Today, inspired by the Civil Rights Movement of the ‘60s and ’70s, the social pendulum has swung toward the appreciation of ethnic and cultural diversity. Chinatown is now singled out as an asset to the urban landscape of the city. Thousands come to visit the same 19th century “exotic heathen temples” with neither disdain nor contempt but with intellectual curiosity, to dine with the locals where once no white man dared to eat the strange odoriferous food. Case in point: when the San Francisco Chronicle on April 20th reported the closing of Sam Wo’s Restaurant, a dirty, rickety, narrow, three-story, one-hundred-year-old hole in the wall condemned by Public Health for conditions unsuitable for the preparation and storage of food, a block-long line of o

ld-time Chinese and non-Chinese customers waited to enjoy a final meal there. Each spring when the parade dragon rears its magnificent golden head, thousands of visitors pack into Chinatown, fascinated with the appearance of a nonassimilated foreign community complete with exotic cultural traditions.

The treatment of Chinatown both in the past and in the present obscures the reality of history. Few realize that the existence of the community is intimately interwoven with the history of the city. The intent of this guidebook is to place the evolution of the Chinese community in the context of the U.S./China relationship and reclaim our rightful place in the annals of America.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It has been a pleasure to work with Garrett Caples, who submitted my manuscript for publication, and Linda Ronan and Jolene Torr of City Lights Books.

I wish to thank Lil Jew for sharing her knowledge of Cantonese operas, Kevin Wong for providing me with articles on his dad, “Woo Woo” Wong, Richard Everett for digging up the 1930 article on the Calaveras County Chinese prefab courthouse, and Dr. Collin Quock for information on the Chinese Hospital.

In all my projects promoting knowledge of the Chinese of America, I have been blessed with the assistance of family members. I’m indebted to my grandchildren, Alexandria Choy and Nathan Wong, and Nathan’s friend Joanna Ho, for spending weeks during summer break from college in 2011, scanning microfilm articles from the library; Jia Wen Wei for being on the spot when I needed help navigating the computer; daughter Stephanie for reading my manuscript to insure that I not loose sight of objectivity by injecting my biases. The photographs of the buildings were taken in 1980 by my son Brian for a case report to nominate Chinatown as a historic district. For months, he was a lone figure on the streets at the early hour of 6:00 a.m., in order to avoid the vehicular and pedestrian traffic and photograph the buildings without obstruction. Finally, a loving appreciation to my wife Sarah of the IBM Selectric generation, who, braving the complexity of the computer, typed and retyped the manuscript.

Philip P. Choy, 4/26/12

INTRODUCTION

The arrival of the Chinese in the United States toward the end of the 1840s was part of an intricate political and economic relationship between Asia and America.

From its birth as a nation, the United States sought to establish itself as a new power among old nations. Many Americans believed in the concept of “Manifest Destiny,” which held that the United States had the right to expand westward across the continent to the Pacific Ocean. The West Coast would be the gateway through which America would acquire and hold the positions of power in Asia.

On the West Coast, in California, San Francisco became not only a major commercial port but also the main port of entry for Chinese immigrants, who were recruited as a source of mass labor for the economic development of the western frontier. Initially, white Americans welcomed Chinese participation in San Francisco’s civic events, such as the celebration, at Portsmouth Square, of California’s admission into the Union in 1850. At the time, the Square was the heart of San Francisco. However, while the City expanded, the Chinese stayed in the area. For over a century and a half, Chinatown has remained in this same location.

The interaction between Chinatown and the community at large has not always been one of mutual understanding. Caught in the struggle between the white laboring class fighting for better working conditions and the industrial capitalists seeking to maintain the status quo, the Chinese became scapegoats for the growing pains of the American labor movement in the West. Sinophobia in the 19th century echoed into the 20th century with the cry “The Chinese must go!” The question of Chinese labor competition occupied a central place in the Nation’s politics for over 30 years, until the passage of the Exclusion Act of May 1882, which in effect closed the door to Chinese immigration.

From time to time, San Francisco attempted to destroy Chinatown and remove the Chinese through both legal and extralegal means. The Chinese responded strategically. When the Board of Supervisors attempted to remove Chinatown after the Earthquake of 1906, for example, the Chinese strove to earn the goodwill of the City by creating a new positive image, retaining architects to transform the neighborhood slums into an “Oriental City.” This new trend of a Sino-architectural vernacular, created specifically as a response to the threat of relocation after the quake, shaped the present skyline of Chinatown.

But Chinatown has always been a tourist attraction. What was sensationalized in the 19th century as a haven for racial peculiarities and cultural oddities is perceived today as an ethnic enclave where cultural habits and traditions are preserved. In either case, the stereotypical image of Chinatown as an unassimilated foreign community remains unchanged. But the significance of Chinatown lies not in cultural exotics. Beneath the Oriental façade is a history rooted in the political past of the City, the State, and the Nation.

That history began following our War for Independence in 1776. The evidence is before our eyes and under our noses if we know what to look for as we tour Chinatown. Tea, ginseng, and the churches take us back to when two peoples of diverse cultures first met, traded, and interacted. In 1784, when Samuel Shaw sailed the first American ship, the Empress of China, into Bocca Tigrus, he traded twenty-eight tons of ginseng and 20,000 Spanish dollars for tea, silk, porcelain, and other treasures. In his journal, Shaw wrote: “The inhabitants of America must have tea … that useless produce [ginseng] of her mountains and forest will supply her with this elegant luxury … such are the advantages which America derives from her ginseng” (Quincy 1847, 231). That historic voyage began our interest in the Far East and subsequently led to frontiersmen’s hunting and trapping off the California coast for the pelts of sea otters for the Canton market. When gold was discovered, the transpacific commerce between California and Canton (now called “Guangzhou”) continued, not only with the importation of Chinese goods for the Gold Rush population but also with the arrival of Chinese laborers from the Pearl River Delta, centered on the City of Canton in Guangdong Province.

From the time of their first encounter in the 16th century, Western nations were determined to open China’s ports to trade. Equally stubborn, China called herself the “Middle Kingdom” (i.e., the center of the world) and attempted to close her doors to the “uncivilized, meddling, barbarians.” By the time of Shaw’s arrival, China had been conquered by the Manchu from Manchuria, who ruled under the title “Ching” (brilliance) from 1644 to 1911. The Manchu adopted Chinese ways and appointed collaborators in government posts to maintain control over the population. After two and a half centuries, the Manchu had been absorbed into Chinese culture, except for the Manchu style of dress and the shaven head with the queue (pigtail), which were forced upon the Chinese as symbols of subjugation.

In 1757, the Manchu Emperor Chien Lung (1736-1796) restricted all foreign trade to one port, the City of Canton. Trading between the Chinese and Europeans was controlled and regulated by Chinese merchants known as Hong, authorized by the Imperial government. Unfair practices, import and export taxes, and the demand for silver in payment for goods created trade deficits among foreign nations doing business in China. To offset the deficits, these nations smuggled opium into China in large quantities. The British, whose merchants had control of the supply from India, dominated the trade. American merchants obtained their supply from Smyrna, Turkey. China’s attempts to stop the smuggling resulted in war with Great Britain (1839-1842). The British easily defeated China and forced its government to open the ports of Canton, Shanghai, Ningpo, Amoy, and Foochow. In addition, the territory of Hong Kong was ceded to England for 100 years.

In the last quarter of the 18th century, glowing accounts published on the exploration and adventures in the South Seas, India, and Africa, not only fired the imagination and curiosity of the public but also aroused the evangelical impulse of Protestant leaders, who founded missionary boards and societies to recruit and send missionaries into the heathen world. While British and American merchants opened the do

ors to the treasures of “Cathay” (China), European and American missionaries envisioned opening the door to the Kingdom of God for China’s three hundred million “heathens.” This missionary enterprise was a part of the Christian revivalist movement known as the “Second Great Awakening.”

Dr. Morrison translating the Bible with Chinese converts, 1820.

At the beginning of the 19th century, this Protestant religious movement led to the founding of the London Missionary Society (LMS), followed by the founding of the American Board of Commissions of Foreign Missions (ABCFM). In 1807, the LMS sent The Reverend Robert Morrison to China and, in 1830, the ABCFM sent The Reverend David Abeel and The Reverend Elijah Bridgman. Canton became the staging area for Protestant missionary activities. These religious activities, together with the long period of commerce with China, promoted knowledge of the West in China, and linked Canton to California. To the Westerner, the Chinese from Canton were known as “Cantonese.” These were the Chinese who would set foot in California when gold was discovered.

Leaders of the evangelical movement quickly realized the strategic importance of California lay not only in the fact that it fronted the Pacific, but also in the unique missionary opportunity the presence of thousands of Chinese afforded; if converted, these Cantonese people could return home to spread the gospel to the teeming millions in China who had never heard the revelation of God. Thus, the many churches in Chinatown today are the result of the efforts of the early Christian pioneers begun in Canton, Macau, and Hong Kong. In San Francisco, the first official evangelical effort took place in a public ceremony on August 28, 1850, when Mayor John Geary and The Reverend Albert Williams invited the Chinese residents to Portsmouth Square to receive religious tracts that were printed in Chinese and published in Canton.

But the fascination with which the West viewed China in the 18th century deteriorated to disrespect and disdain by the 19th century. Following its defeat in the Opium War with England, China under the Manchu rulers was on the verge of collapse. Unable to deal with the belligerent demands of Western powers, the government adopted a foreign policy of appeasement, granting concession after concession. Foreign exploitation, internal rebellion, and overpopulation accelerated the decline of China’s economy and the deterioration of social conditions.

San Francisco Chinatown

San Francisco Chinatown